Productivity hacks can help you focus on what really matters, use your time effectively, and make progress on big projects. But here are 3 popular techniques that don’t work for everyone or in every situation, and the alternatives you could try instead:

1. Become an early riser. Waking up before sunrise is a habit for many successful go-getters. Richard Branson (founder of Virgin Group), Tim Cook (Apple CEO), Oprah, and many top CEOs begin greeting the day before 6 am. The extraordinary Benjamin Franklin coined the adage, “Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise,” and was a prolific early riser.

Research suggests there are psychological and physical benefits to waking early. In his 2009 article, Proactive People are Morning People, published in the Journal of Applied Psychology, biologist Christopher Randler notes that morning people are more proactive than evening types, i.e. they are more willing and able to take action to change a situation to one’s advantage. In a survey of 367 university students, Randler found that a higher percentage of early risers agreed with statements that indicate proactivity, such as “I spend time identifying long-range goals for myself” and “I feel in charge of making things happen.”

A 2008 study at the University of North Texas in Denton found that early birds tend to have GPAs that are an average of one point higher than their night owl peers’. The author Daniel J. Taylor theorized that early bird students are less likely to engage in activities that negatively affect their academic performance.

From a productivity standpoint, waking early has advantages. “Your most valuable hours are 5 a.m. – 8 a.m. They have the least interruptions,” says Robin Sharma, leadership expert and best-selling author of The Leader Who Had No Title. Productivity speaker Jeff Sanders also recommends you join the 5 a.m. Club to make maximum use of the morning hours, when your willpower, focus and energy are typically at their peak. His 5 AM Miracle podcast is “dedicated to dominating your day before breakfast.”

Early morning – before the rest of the world wakes up – provides quiet, uninterrupted time for focused work. Being an early riser also fits with the regular, 9 to 5 schedule that applies to most of the workforce. When you tackle your tasks early or to-dos first thing in the morning, you generally feel more productive and less stressed throughout the day.

But membership in the 5 a.m. Club is not ideal for all and can be painful to maintain. When I shifted from a 7:30 to a 5 a.m. wake-up time for a few months, I loved the new schedule. I made the change gradually in 30-minute increments each week. The shift involved moving to 7 a.m. in week 1 and all the way to 5 a.m. in week 5. My desire to do focused work before my preschooler woke up was the driving factor.

Waking up before sunrise was not the problem, but going to bed earlier was. Whenever I got less than 7 to 8 hours of sleep, I would naturally feel groggy in the mornings and tired by afternoon. So I had to be asleep by 10 p.m. each night to be a full-fledged member of the 5 a.m. Club. This meant preparing or having dinner earlier (and making changes in family/social time), compromising on evening rituals, and losing out on the creative insights and deep reflection that accompany being awake after 10 p.m. As a result, I now wake up between 6 and 7 a.m., which gives me an hour or two of quiet time in the mornings without needing to keep a super early bedtime.

Alternative: You don’t have to wake up at 5 a.m. every day to be super productive. Instead, keep a consistent sleep schedule that fits with your personal chronotype (biological clock or circadian rhythm), the earth’s 24-hour cycle, and your individual circumstances.

When you wake up is not as important as how you feel and what you do during your waking hours. You first have to figure out the ideal amount of sleep you need to feel refreshed and alert during the day. (Most adults need at least 8 hours of sleep, although many get by with less by consuming artificial stimulants.) Set yourself up for high-quality, sufficient slumber by going to bed — preferably at an hour before 12 AM when you have the opportunity to get all the non-REM and REM sleep you need — and waking up after you have had enough shuteye.

Develop a morning ritual to prime yourself for the rest of your day. No matter what time you wake up, create a solid plan for prioritizing your day and stick to it.

If you’re not an early riser but want to become one, you need to clarify the why behind this desire. You can’t expect to rewire your brain and sustain change by blindly following productivity advice. Make the shift incrementally (through habit formation) instead of overnight (through sheer willpower).

2. Schedule your priorities. Many productivity experts say you should schedule time on your calendar to work on your to-dos. Some believe that to ensure the thing gets done, it needs to be scheduled.

Kevin Kruse, author of 15 Secrets Successful People Know About Time Management, recommends you nix the to-do list altogether and schedule everything. Michael Hyatt, author of Living Forward: A Proven Plan to Stop Drifting and Get the Life You’ve Always Wanted, maps out his Ideal Week on a calendar. He schedules time for his most important tasks, weekly appointments, special projects and quarterly reviews. Both Kruse and Hyatt advocate scheduling non-negotiable me-time or buffer time for yourself.

While carving out time on your calendar can boost productivity, it’s not foolproof. Interruptions and distractions get in the way. Energy levels dip and attention spans dwindle. Over-scheduling can suck the joy and spontaneity out of life. Although a calendaring system helps you stay on task, it can sometimes create too much rigidity for when to accomplish your to-dos. If you didn’t perform the task as scheduled, you’ll use up time reworking your calendar and feeling dissatisfied over unfinished business.

Alternative: Using both a to-do list and a calendaring system is an effective, combined approach to making progress on your important projects and fulfilling your commitments. The to-do list is for tasks that do not have to be done at a specific time. The calendar is for activities that must occur at an allotted time.

For example, I schedule only meetings and appointments on my calendar, and plug away at my one to three Most Important Tasks (MITs) (usually related to research, writing, and problem solving) during set time blocks (e.g. 8 to 10 am, 2 to 3 p.m. and 5 to 6 p.m.) I don’t give in to interruptions and distractions when I am engaged in focused work. The other hours are for ad-hoc activities and shallow work, like responding to emails and making telephone calls. This combined to-do/calendaring system provides structure without needing to schedule every single task on your calendar.

Adhering to a fixed schedule is less critical than doing your most difficult work when your mental clarity and focus level are at their highest. Consider the output you contribute, not the hours you put in. Pace yourself by taking necessary breaks. Work around your energy instead of force your to-dos into a rigid schedule. Even with this more flexible approach, you can still keep a shutdown time – when you stop doing work and start winding down – to avoid burnout and impaired productivity.

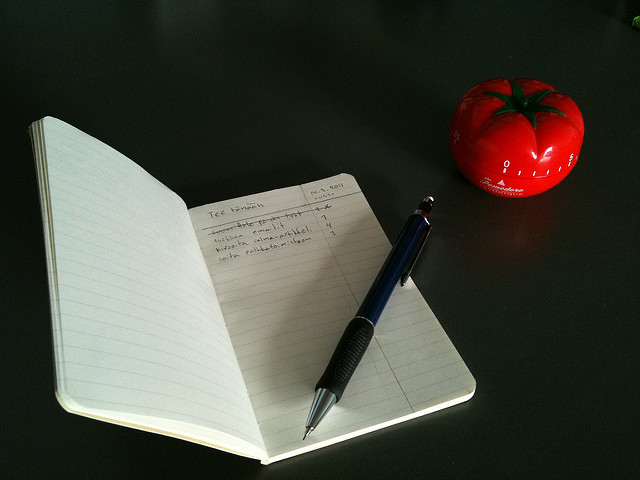

3. Use a timer to focus on a task. The “Pomodoro Technique” is a time-management method that was developed by Francesco Cirillo in the late 1980’s. “Pomodoro” is the Italian word for tomato. Cirillo adopted the name from the tomato-shaped kitchen timer he used to manage his time as a college student.

The Pomodoro Technique involves several steps. First, you identify the task to do. Second, you set a timer (traditionally 25 minutes). Third, you work on the task only until the timer goes off. After the timer rings, you check off your task. And if you give in to interruptions and distractions (e.g. checking emails, getting a snack), you reset the timer. If you have fewer than four checkmarks, take a short break (5 minutes), then go to step 2. If you have at least four checkmarks, take a longer break (15–30 minutes), reset your checkmark count to zero, and do the steps all over again.

The technique helps you to set aside time and space to work on a single task and avoid procrastination. Having a timer adds a sense of urgency and importance to getting the task done. The breaks between tasks also allows you to preserve your energy and sustain your focus over long periods.

The technique, however, can also cut into your workflow and make it harder to develop the skill of doing real, deep work. The ability to concentrate on hard things for extensive periods takes practice to develop. If you’re constantly taking breaks (e.g. every 25 minutes), you don’t learn to sit with and push through temporary moments of discomfort or boredom.

Relying on a timer can also reduce your awareness of when it’s really time to call it quits. The technique can force you to work for sustained periods, when your mind is wandering off or your body is fatigued.

Working under time pressure can work for some people and for some situations. But when you get pulled into watching the timer instead of focusing on the task at hand, the Pomodoro Technique backfires.

Alternative: Single tasking and taking regular breaks — while nixing the timer or the 25-minute rule – provides the benefits of the Pomodoro Technique without the drawbacks. If you find it difficult to focus on one task at a time, you can use Pomodoro to get you on track. You’re better off though when you eventually tailor the method to your personal preferences.

Experiment with the duration of your work sessions. For certain low-value, administrative activities, like processing emails, you might want to stick with 25 minutes followed by a 5-minute break. And for high-value, deep concentration activities, you could work in a 90- to 120-minute cycle, which is the brain-body’s natural ultradian rhythm, before taking a 20-minute break. Standing up and stretching for just a minute every 45 minutes can also help you avoid long periods of being desk bound or holding bad posture, which is detrimental to your health.

When you’re in the zone, you don’t have to break your workflow with a mandatory break. Pay attention to your energy level. Take breaks based on the state of your mind and body, rather than depend on a timer. During your break, engage in activities that clear your mind (e.g. take a walk or meditate) and avoid activities that clutter it (e.g. surf the Internet or check social media).

Test out productivity hacks and use what works for you

There are many productivity hacks from which to choose, but only a few are ultimately right for you. Try the method or technique for at least 30 days before you give up on it because you are bound to experience resistance and setbacks initially.

Experiment, make use of the ones that fit, and drop the ones that create more stress. Develop a customized, personal productivity system that helps you focus on and accomplish what really matters. Sometimes a simple tweaking of existing systems is all you need to do.

# # #

Photo by: Jussi Linkola